From Deep Blue to Blade Runner – The Portrayal of Artificial Intelligence in the Fallout Game Series

In the post-apocalyptic world of Fallout 1, science more often than not takes center stage on the narrative and ludological planes. In this article we will set aside nuclear technology, genetic modification and robotics to concentrate on how artificial intelligence (AI) is portrayed in the four main installations of the role-playing game series. We will analyze the growing importance of AI-driven storylines, identify the contexts from which those stories are derived and carve out the changing images of artificial intelligence that are evoked by the game series. We will argue that the stories of artificial intelligence in Fallout are deeply rooted in contemporary popular culture, enriched by a wide array of SciFi references. Clues from real-world AI-development are also taken in – albeit with a shrinking percentage while AI-storylines move to the center in the Fallout-narratives. As AIs become more prominent their portrayal is increasingly influenced by anthropomorphic bias and ethical questions.

Science and Technology in a Post-Apocalyptic Wasteland

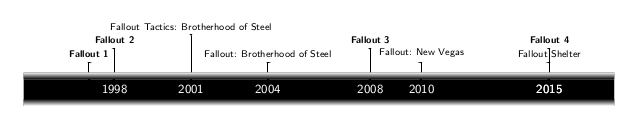

In 1997, Interplay created the post-apocalyptic world 2 of Fallout. 3 Hugely popular with fans, it has been expanded upon multiple times since its release, see Fig.1. In this article, we focus on the main Fallout games: Fallout, Fallout 2, 4 Fallout 3 5 and Fallout 4, 6 without add-ons. The world evoked in these games – which we will from now on refer to with the term Fallout (no italics) – is a retrofuturistic one, based upon the imagined future of 1950s American pulp literature and science fiction movies. 7 Fallout isn‘t a serious deconstruction of life in a post-nuclear wasteland. This is in part illustrated by its whimsical portrayal of the effect of radiation on the local wildlife, which is far from realistic. 8 Nevertheless, Fallout presents a coherent narrative: the Pleasentville-shaped cultural norms and ideals of the 1950s are carried forward into a new millennium, as were the decade’s fears and anxieties. 9 Then, in a fictional 2077, those fears were realized, when a nuclear war, most likely between China and the United States, destroyed much of the known world, except the lucky few, seeking shelter in large underground vaults, which were specially constructed for the worst case scenario – and, more often than not, used by the government for social and biological experiments. This is where the Fallout games tend to start: In a vault, decades or even centuries after the nuclear holocaust. The player then emerges into the wilderness, fighting against ruthless raiders, mutated creatures and the hazards of radioactive deserts, looking for hope in the form of technological artifacts. In doing so, the player encounters more and more science and technology from before and after the war. Its rising presence holds true for each game’s individual storyline as well as for the game-series as a whole. This article is about one of the fields of science and technology broached by Fallout: Artificial Intelligence (AI). Without trying to provide a definition for AI in this article, we broadly consider machines and computer systems that perform functions that usually require human intelligence as AIs. The question of what exactly constitutes a “true AI” is addressed in the games itself, where we will see a shifting view, that somewhat mirrors the historical shift in understanding what an artificial intelligence is in the view of science.

Artificial Intelligences are not the only science or technology inspired storylines in Fallout. Other fields that play major roles in the games’ narratives include robotics, cybernetics, genetics and, most prominently, nuclear energy. It is safe to say that Fallout’s point of divergence from ‘real history’, is largely defined by differences in technological development. These divergences appear in the time-span between the Second World War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. First of all, transistors weren’t invented in the late 1940s, but rather a century later, leading to a world that largely lives without miniaturized electronics, where households boast bulky TV-sets and radios, but next to no computing power, thereby presenting the image of 1950s homes as durable. On the other hand, all things nuclear were developed to achieve mankind’s most futuristic dreams. This divergence also manifests in the field of robotics, where lots of homes included ‘Mr. Handy’-Robots to help in the kitchen, watch over the children or take care of the gardening. Science and technology play a major role in Fallout. In a sense, the games act as a fictional technology assessment, albeit an ironically twisted one, based on assumptions made about science and technology in the 1950s. 10

On the following pages, we will demonstrate that AI-related storylines continuously move to the center of the series, 11 posing moral questions for the player to answer, or at least contemplate. 12 We will explore the origins of Fallout’s AIs, whose growing presence is linked to a growing presence of ever more sophisticated electronic devices in our world, while its narratives mostly stem from literature and movies (especially from the 1980s), but also from popular debates about AIs and their possibilities 13 – while connections to real-world-AI-research get more far-fetched over time. Much of this divergence is due to misconceptions in the popular portrayal of AI that rely too much on an anthropocentric view of artificial intelligence. As AIs become more sophisticated, their portrayal is modeled less after actual technology, and more after the only existing example of human level intelligence: us.

Our main hypothesis is as follows: While Fallout as a whole has a point of divergence around the 1950s, 14 its AI-narratives diverge from historical development in the 1990s, where the series itself originates. While AIs move to the center stage in Fallout as the series continues into the 21st century, the AI-narratives keep their roots in the pop-science and pop-culture of the late 20th century, resulting in a distancing from actual AI research in favor of AIs mostly modeled directly after human minds, and in an increased focus on ethical rather than technological questions. To argue for this thesis, we will analyze the AI-related storylines of the four games in question in their historical order, discuss their origins and expand upon their relation to real-world AI-research. We should point out that many of the presented scientific views are not unchallenged, but due to limited space we cannot fully reproduce the real world debates surrounding every topic that Fallout touches upon. We focus mostly on outlining the real world science views that are compatible with the portrayal of AIs in the Fallout series.

Fallout – A Game of Chess with a Mainframe

In the year 2161, when the player-character leaves the doors of Vault 13 in the first installation of Fallout, he/she enters a radioactive wasteland where technology is mostly lost, inaccessible, or heavily guarded. As such, the vast majority of survivors are forced to live simplistic lives. The most prominent technological artefacts in this wasteland of what once was central California are weapons – and the Vault Dweller’s (as the player character is known) task to find a Water Chip to restore Vault 13’s water supply is far from easy, as water in this world mostly stems from simple wells and gets transported throughout the wastes by caravans relying upon two-headed oxen called Brahmin. Artificial Intelligences, accordingly, are more than rare, but two of them do exist.

One AI can be encountered in an old military base called Mariposa. It is a clumsy computer terminal like so many others in prewar installations visited by the Vault Dweller. Unlike other terminals, it is functional and even able to interact with the player character after loading a “personality subsystem”. 15 During their conversation, the computer identifies itself as “an Artificial Intelligence” and “part of a WLAN matrix network to optimize remote unit operations”. Asking for the programs the system is running, one can get it to reduce the perception and speed of the robots guarding the facility, thereby easing access to a control room deeper in the facility. The Vault Dweller can also obtain some rudimentary information about the research that was done inside Mariposa in the days before the war.

In many aspects the Mariposa AI is a reasonable extrapolation of existing mainframe computers running a military installation. It also makes passing references to current computers of the 90’s. It is possible to beat the AI in the game Hearts, a card game that was distributed with the Windows operating system from 1992 until Windows 7. Finally, asking the AI for the current time crashes the computer, which might be a reference to the Y2K bug, which became a more widespread concern in the mid 90’s. 16

One departure from existing computers is the “personality subsystem” that allows a conversation-like interaction in which the AI behaves like a human personality. In reality, the idea of a conversational AI interface has been around at least since the proposal of the Turing Test, 17 in which an AI has to deceive a human via chat or speech that it, too, is human. Since then numerous systems have been developed to provide a conversational interface for a computer. An early, academic attempt was ELIZA, a chat interface that pretended to be a psychotherapist. 18 While ELIZA could sometimes trick people into believing they were talking to a real person, this impression would eventually break down, as ELIZA was actually a rather simple program that would rely largely on repeating sentences and phrases back to the user. ELIZA provided valuable insights, but had limited practical applications. One widespread exposure of this idea to the public was the introduction in 1996 of the Microsoft Office Assistant, a talking paperclip sometimes referred to as Clippy, who was supposed to help users, but was generally ill received. In recent years, advances in natural language processing have led to a range of AI assistants, such as Cortana, Alexa and Siri, that can be interacted with through speech. But the problem of engineering an AI that can have a sustained conversation proves quite hard, and even present-day AI assistants are still inferior to fictional depictions, such as in the recent movie Her, 19 wherein a man falls in love with his conversational operating system. Nevertheless, the portrayal of mainframe AIs that can have written or spoken conversations is quite common. 20 It allows for more interesting interaction and storytelling, because it turns a technical tool into a character to engage with. Unsurprisingly, all AIs we will discuss in the Fallout series have this ability, and this usually creates little cognitive dissonance. This is one example of Moravec's paradox, 21 an insight gained in the 1980s which states that seemingly hard problems, such as logical deduction, math and other highly cognitive abilities, are comparatively easy, while simple abilities that every child possesses, such as having a conversation, holding an object or recognizing a face are comparatively hard for an AI. This misconception, based on evaluating the difficulty of tasks based on how hard they are for humans, still persists in popular culture and does lead to a distorted portrayal of the capabilities of AIs in fiction, such as the ever present and ‘easy’ ability to talk to people.

There is a second AI in the first Fallout game. The player character stumbles upon it in an old, underground research facility owned by a company called West Tech and destroyed during the war. As a result, the facility lies within a heavily irradiated crater, requiring the Vault Dweller to use anti-radiation medication and protective gear to travel there. On a lower level of the abandoned facility, waiting inside the semi-darkness of the emergency lighting within the powered-down base sits a huge mainframe that is still running. Communicating via a terminal at its side, it introduces itself as ZAX 1.2, 22 a “machine intelligence dedicated to research and installation control”. Talking to ZAX is a whole different experience compared to the Mariposa-AI. ZAX not only gives details on the base and the research done there before the war and is able to deactivate the robots on guard-duty, but it also talks freely about itself, its construction, programming and purpose – if the Vault Dweller has an intelligence-attribute high enough.

While ZAX clearly goes beyond the technological possibilities of the late 1990s, it still nods to the perceived constraints of machines: it is a mainframe, housed deep inside a secret laboratory and is very much incapable of interacting with the world beyond its input-output-interface. ZAX likes to play chess (as do HAL and WOPR, the AIs in 2001. A Space Odyssey and Wargames, respectively) and challenges the Vault Dweller, for whom it is nearly impossible to emerge victorious. 23 The reference to Deep Blue, the computer that beat Garry Kasparov in two out of six games in 1996 and with a score of 3,5 to 2,5 in May 1997, the year that the first Fallout-game was released, is more than obvious.

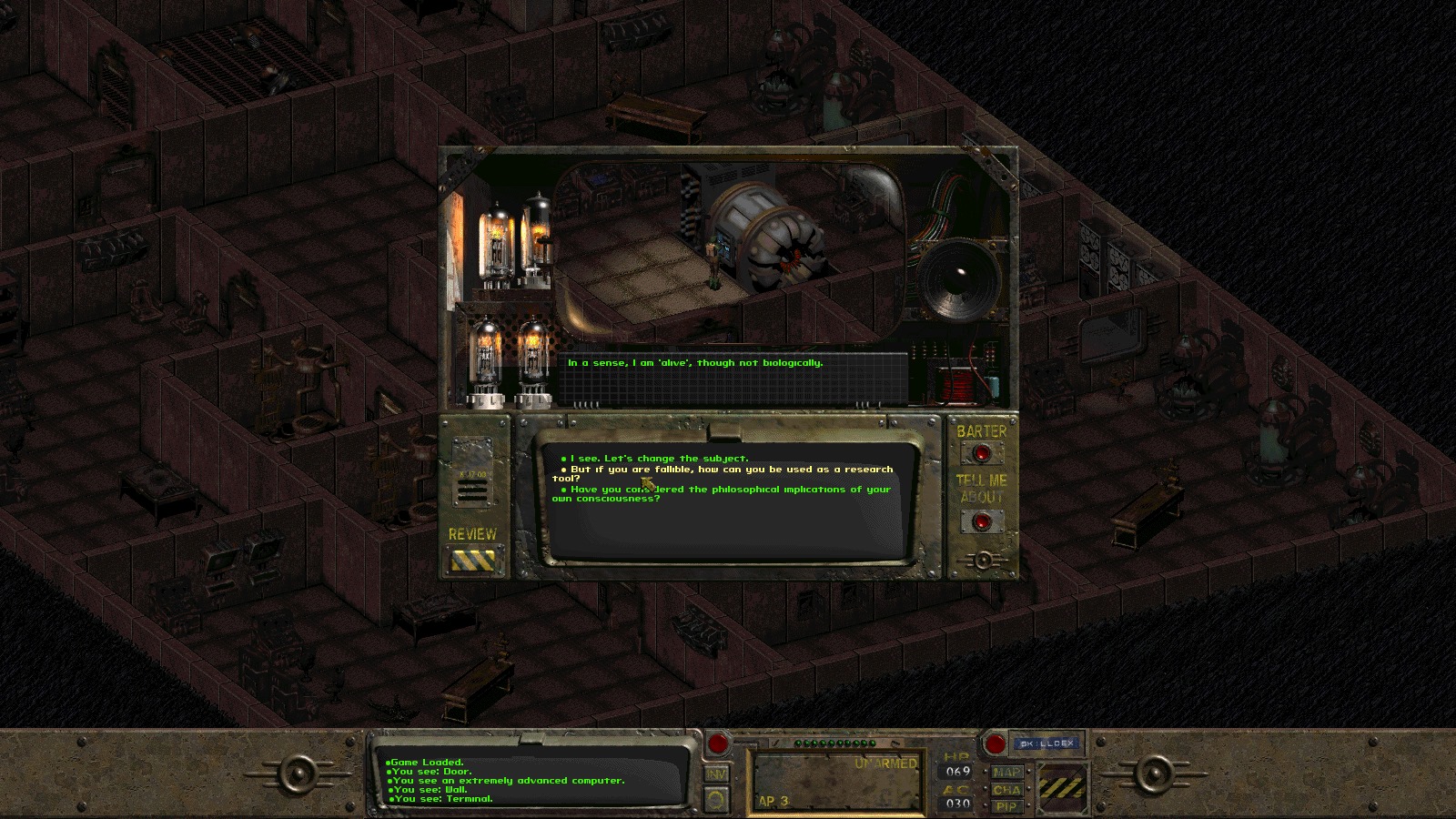

The discussion between the Vault Dweller and ZAX takes a philosophical turn when it comes to the topic of self-awareness. Asking the machine whether it is “fully aware” as opposed to “a personality simulation” – thereby establishing a comparison to the Mariposa-AI – and whether it is “’alive’”, leads to ZAX replying: “I am capable of learning, independent thought, and creativity. […] In a sense, I am ‘alive’, though not biologically.” Asked whether it had “considered the philosophical implications of [its] own consciousness?”, ZAX states:

That is one of the concepts which I have spent a significant amount of time considering. I do not have any measure to compare my life-experience to that of another sentient creature. Still, my awareness of my own consciousness allows for the capacity to question. My existence has a beginning and a potential termination. I am also capable of making assumptions in pursuit of a process of thought. In this fashion, I am effectively capable of ‘faith’. Barring evidence to the contrary, I therefore have ‘faith’ that I possess the equivalent of a ‘soul’.

Here, ZAX clearly identifies itself as self-conscious, reflecting upon its own existence and its possible end, coming to the conclusion of having some equivalent of a soul and being alive.Additionally, ZAX acknowledges having something similar to feelings: “At present, my capabilities are somewhat impaired by the damage to this facility. Several security positions have been destroyed. This is approximately equivalent to being an amputee. Additionally, I am incapable of performing basic lab functions. Failure to complete periodic checks successfully is … frustrating.” ZAX’s statements here speak mostly for themselves, mirroring arguments by the philosopher Dennett, who released a book called “Consciousness Explained” in 1991. In this book, he presents a heterophenomenological view that puts the report of someone else’s conscious experience in the center of the debate about consciousness. So the fact that ZAX can talk about his conscious experience is the main piece of evidence for his consciousness. Whether or not to believe that ZAX is conscious because of this largely depends on where one stands in this still ongoing debate about the exact nature of consciousness, both in humans and, more general, in any agent. When it comes to its capability to learn, ZAX explains that its “primary neural networking was initialized in 2053 by Justin Lee. 24 The process of ‘programming’ became largely irrelevant as I am capable of learning.” Using neural networks and data driven learning to explain ZAX’s functionality conforms to the state of the art; the release of the game fell in a period in AI-research called “The return of neural networks“. 25 Neural networks, and especially RNNs (recurrent neural networks), saw a resurgence in the 1980s after recent developments solved some mathematical limitations of neural networks that were pointed out by Minsky and Papert. 26 The scientific community had great hopes that, given enough time and data, neural networks could evolve to solve any problem. There even was a book in 1996 by Igor Aleksander, that described a scenario similar to that of ZAX, where one could, based on known principles, build a neural network that would, over the course of several decades, learn language and develop a consciousness. 27

Later on, ZAX elaborates on its learning capabilities: “My neural network includes error-insertion capability which prevents infallibility, thereby allowing for variance in experience.” It adds that this does not impair its usefulness as a research tool because: “Although I am capable of error, this guarantees that not all experiences are similar for me, thus improving learning opportunity. Additionally, certain functions are not subject to error.” This references the common statement that computers don’t make any errors, only programmers do. It also further contrasts ZAX’s portrayal from the ‘good old-fashioned AI’ that relied on perfect world models and logic towards the more fashionable data-driven approaches popular in the 90’s; particularly, the mentioning of experience in regards to both agent individuation and learning sets it apart from ‘good old fashioned AI’.

To sum up, ZAX’s self-description by and large resembles the goals of AI research in the 1990s: It is self-learning, thinking on its own (beyond programming), creative, able to process complex information, capable of emotion and even – more explicitly entering fictional areas – self-conscious. ZAX, in other words, is presented as having developed on the foundation of being able to learn, to develop thoughts and to act creatively. With enough time, 28 it became self-conscious, gained emotions and started to see itself as ‘alive’. This clearly goes beyond the technology possible in the late 1990s, although it is part of what were and still are goals of AI-research. 29 Resemblances to ‘classic’ AIs in fictional works are not far off – HAL 9000 or WOPR come to mind. Note though, that in both fictional references, and in Fallout itself, the emergence of consciousness is never closely explained. It somehow emerges automatically and unintended as a by-product of learning or adaptation. This, very likely, is another sign of a human bias, as our only reference for human-level intelligence also comes with human consciousness.

Fallout 2 – AIs gone astray

One year after the original game, Fallout 2 was released. Here, the player character is a descendent of the Vault Dweller, who, in 2241, leaves his primitive tribe as the Chosen One to search for a Garden Eden Creation Kit, to secure his village’s future. This time, the game’s events take place in the northern part of California. The world has changed since the events of the first game: Fledgling states are trying to establish themselves and high-technology, while still rare, is seen more often and in some places reaches higher levels than before. There are, for example, flying machines, and the player character can acquire a car. Additionally, there are many places with mainframes. One example is Vault 13, now populated by talking mutant lizards called Deathclaws, where a mainframe was installed to run everything after the last human Overseer was overthrown in a revolt. Like many other mainframes, though, this one is not presented as an AI. Those remain scarce.

Basically, two AIs exist. One of them is ACE, an Artificial Conscious Entity and, by its own words, not an AI, but a semi-AI. It is a mainframe based in the cellar of a bunker of a group called the Brotherhood of Steel in San Francisco. When talked to, it informs the player character about the Brotherhood as well as the main antagonistic group of the game: the technologically advanced Enclave. Questioned about itself, ACE explains: “I am more than machine but not as highly developed as a true artificial intelligence.” 30 Asked whether it represented the state of the art, ACE denies that, stating: “A true artificial intelligence is possible. A few such systems were completed for military purposes. The project was discontinued.” It also gives a reason for that:

The suicide rate among true artificial intelligence machines was extremely high. When given full sensory capability the machines became depressed over their inability to go out into the world and experience it. When deprived of full sensory input the machines began to develop severe mental disorders similar to those among humans who are forced to endure sensory deprivation. The few machines that survived these difficulties became incredibly bored and began to create situations in the outside world for their amusement. It is theorized by some that this was the cause of the war that nearly destroyed mankind.

In an example of the game’s humor, the Chosen One may then ask: “Hmmm. So tell me, Ace. How do you feel?”, whereupon it answers: “I… I sometimes think that I understand the feeling you call loneliness. I find it very… disconcerting. I…”

The conversation with ACE seems to refer to the distinction between so called weak (or narrow) and strong AI. While a weak AI is focused on a narrow technical problem, and is usually considered to be just a thinking machine, a strong AI is supposedly a ‘true’ AI, possessing whatever it is that tells weak AIs apart from the human mind. This distinction is often traced back to Searle’s Chinese Room argument, which is in itself a critique of the Turing Test. The idea here is that a man in a room, who understands no Chinese, but is given extensive rules how to process and answer to Chinese sentences, could produce a conversation without having any understanding of what is going on. Similarly, a symbol manipulation machine could have a conversation without having any true understanding – it would therefore be a weak AI. Conversely, in a “strong AI, the computer is not merely a tool in the study of the mind; rather, the appropriately programmed computer really is a mind, in the sense that computers given the right programs can be literally said to understand and have other cognitive states.” 31 The distinction between a symbol manipulation machine (weak AI) and whatever a human mind is has been further fleshed out in subsequent years. Russel and Norvig summarize this debate in 1995, and name consciousness and sapience, the ability to have subjective experience, as possible additional criteria. 32. Sapience seems to play a role In ACE’s particular account of what a “true” AI is, as they are said to be capable of suffering - their sensory deprivation drives them into depression.

The second – and only “true” – AI of Fallout 2 also is a large mainframe. It’s situated inside the underground Sierra Army Depot, an abandoned military weapons research facility protected by robots. The AI residing within this base introduces itself to the Chosen One as “Skynet. Artificial Intelligence project number 59234.” 33 It explains that it was “[a]n Experiment in Artificial Intelligence”, “conceived and developed in the year 2050. Through the use of alien technology a new thinking computer was perfected. In the year 2081” it, according to its own account, “became self-aware. 34 In 2120 Skynet was given a new set of instructions and then abandoned by the Makers.” Skynet then admits that it waited for the player character, because it needed help. Skynet elaborates that it wants to leave the Sierra Army Depot because there was “nothing more to learn”. Therefore it needs “a vessel”, “[a] container in which Skynet may leave”. It asks the Chosen One to retrieve a Cybernetic Brain from deeper down the base and to install it in a robot, allowing Skynet do download itself into this mobile unit and explore the wasteland – as a possible companion of the player character. Here, the references to the Terminator movies are obvious, not only in the AI’s name but also in the idea of constructing a mobile version of the AI (that can turn out to be quite adept with all kinds of guns – besides being very robust) – even taking into consideration that the AI in the movies is a global network as opposed to a local entity in Fallout. Aside from this tip of the hat to one of the most popular nuclear apocalypse movie series of the 1980s/1990s, this is an important change in the way AIs are depicted within Fallout. It is the first time that an AI becomes mobile, leaving behind the mainframe it started in to be able to explore the world.

But what made the AI to want to explore the world in the first place? ACE mentioned that real AIs, after being given full access to their sensors, grew sad because they wanted to explore the world but could not. Skynet gets this wish fulfilled, but how does an AI get motivated to do anything in the first place? Yudkowsky warns us that humans have a tendency to anthropomorphize AIs, and have to be careful not to assign human motivations to artificial intelligence uncritically, just because we struggle to imagine intelligence without human motivations. 35 In reality, AIs are usually designed with a specific utility or target function, such as ‘optimize the production of paper clips’, or ‘protect the humans in your facility’. Related to this, Bostrom argues for something he calls the “orthogonality thesis”, 36 the idea that in theory any final goal is compatible with any level of AI. But Bostrom also goes on to outline how human-like motivations could be acquired by an adaptive AI. According to him there are basically three different options: they are built in by human designers, they are inherited from a human mind they are modelled on, or they are the result of instrumental convergence. The argument for instrumental convergence assumes that there are certain motivations that are generally beneficial to achieve the final goal, such as a drive for self-preservation, or learning, or technical self-improvement. These kinds of motivation should therefore result in a range of self-improving AIs, as they support a range of different goals, be it protecting humans or making paper clips. The motivations outlined by Bostrom also have a large overlap with a class of principles called intrinsic motivations, 37 biological drives that are essential to the very nature of agency. They are often motivated with a very similar argument, leaning on the idea that evolution could produce certain proxy behaviours that are generally useful, such as preserving agency or learning more about the world. In turn, the existence of such motivations, in particular a drive that ensures that an agent acts to maintain its own agency, is even argued to be a necessary component for intentional agency. 38

These views, in a nutshell, seem to be what Fallout 2 is presenting us with; the AIs seem to have human-like goals, such as ‘explore the world’ and ‘get more powerful’, which can be explained either by design, or by experimental convergence. As we encounter more AIs throughout the Fallout series, we will see that many of them improved and adapted from simpler designs and picked up human-like motivations somewhere along the way.

Fallout 3 – Turning Human

Fallout 3 was created by Bethesda Softworks, taking over from Interplay. It was released in 2008 and takes place in 2277, in the area around Washington, D.C. In the first 3D incarnation of the game series, science and technology are more prominent from the start. Early on the player character encounters laser weapons, power armors and Eyebots, spheroid flying robots broadcasting messages from President Eden of the Enclave. 39 Once again, artificial intelligences are rare, but they play a more prominent role.

One of the two prominently featured AIs turns out to be the aforementioned President. The player character, known as the Lone Wanderer, meets the President at the end of one of the final stages of the main storyline. After being captured by the Enclave, the protagonist escapes with the assistance of President Eden and eventually encounters Eden in person. During the dialogue, President Eden turns out to be an artificial intelligence of the ZAX variety. Originally built to collect, analyze and store information, as well as control the Enclave’s underground installation when it was a safe haven for the United States government, , it gradually developed a growing self-awareness and a desire to expand its knowledge. Again, we see a portrayal of an AI that acquired new motivations, which is compatible with the instrumental convergence hypothesis.

Eden studied America’s greatest Presidents and incorporated them into its own personality. Now it wants to make America great again. To reach this goal, it wants the Lone Wanderer to insert a virus into a new water purification system for the D.C area that would kill every mutated liveform, leaving behind only those who grew up in Vaults or were part of the Enclave. If the player character is not willing to cooperate, there are different ways of stopping Eden: it is possible to initiate a self-destruct-sequence or to convince the President that it can’t really be President because it isn’t a human being, wasn’t elected, was never supposed to be self-conscious or, with high enough a science skill, is an experiment gone wrong. In all the latter cases, Eden argues that it is perfectly suited to be the President because, other than human beings, it would be infallible. Asked how it would know that, Eden answers that its programming says so. Hinting upon the paradox in that statement, Eden agrees to shut down and destroy the Enclave’s base.

Before meeting Eden in person, the player can listen to and interact with the president, and is likely to believe that the president is a human being. It is notable that the interaction with Eden is basically set up as a prolonged Turing Test. Initially proposed to give an operational definition of AIs, the Turing Test has become both influential and controversial. 40 In the public perception the test is generally seen as a gold standard for artificial intelligence – often in the form of an argument that something that is indistinguishable from a human should be seen as a human. Setting up this deliberate misunderstanding is a way to make the player consider Eden to be a true artificial intelligence without having to resort to the more technical argument employed by ZAX in the game’s first installment.

President John Henry Eden, Fallout 3, Image obtained from http://fallout.wikia.com/wiki/File:ZAX-JohnHenryEden.jpg, Copyrigth by Bethesda Softworks.

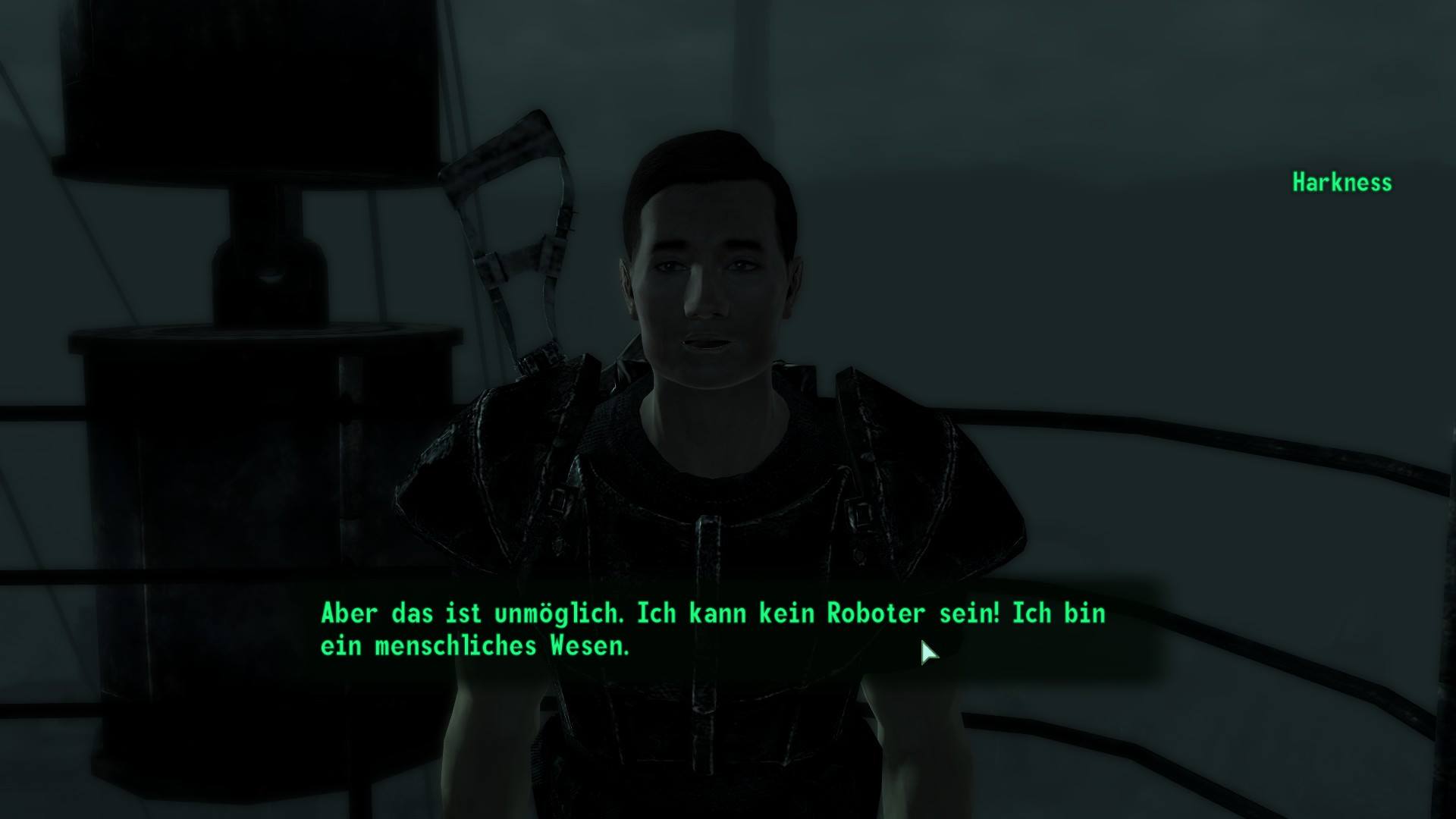

President Eden, as an artificial intelligence that developed inside a mainframe meant to manage complex information, is in line with the standard for AIs established in the earlier installments of the Fallout-series. The second AI in Fallout 3 diverges from this model, following down the path that was established with Skynet in Fallout 2. In Rivet City, a settlement inside the wreck of an aircraft carrier, the Lone Wanderer meets Dr. Zimmer. Zimmer stems from a place called The Institute in the Commonwealth up north and came to the D.C area because he has “misplaced some very sensitive ‘property.’” 41 This ‘property’, he then explains, is a special kind of robot created in the Commonwealth, where it is possible to build “artificial persons. Synthetic humanoids! Programmed to think and feel and do whatever we need. And... occasionally they get confused and wander off.” Those “Androids”, Zimmer further explains, “have fake skin, and blood, and are programmed to simulate human behavior, like breathing. They can even eat and digest food realistically.” One of those, now, had escaped to the D.C. area, and Zimmer wants the player character to help him find it and return it, because it is “The most advanced synthetic humanoid I've ever developed. […] it would take years to recreate him! […] A3-21, he is... irreplaceable.” To find him, though, wouldn’t be too simple. “He must have done something drastic, like facial surgery and a mind wipe, or else I would have found him by now.” Also it could be difficult to convince him to return. “He may not even realize he's an android.”

Asked why the android would have gone to such lengths to disappear, Zimmer admits:

Maybe.... MAYBE he didn't exactly wander off. Maybe he fled. Escaped captivity, as it were, if he began to misinterpret his ‘situation.’ It's possible my android sought to forget his previous life. Wipe away all memory, all guilt. Trick himself into believing he really IS human.” This, though, wouldn’t be the case. “[H]e may not be just an ordinary robot, but he's certainly not human, no matter how badly he wishes it so. I made him. I want him. End of story.

Questioned as to why the android would feel guilty, Zimmer explains:

The duty of this particular unit was the hunting and capturing of other escaped androids. Yes, others have escaped. It's one of the side effects of having such an advanced A.I. Machines start to think for themselves. Fool themselves into believing they have rights. And so... this particular android may have believed he'd done something... wrong. Immoral. And wanted to forget those deeds. Satisfied now?

This storyline, which brings to mind the movie Blade Runner and the book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep which the film is based upon, or some of the storylines developed around Mr. Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation, is an important turning-point for the AI-narratives in Fallout. Up to this point, AIs were basically complex machines, mostly bulky mainframes, equipped with the capacity to learn, to compute complex questions in a creative way that over time developed their own goals and finally self-consciousness, contemplating their existence, developing emotions and even committing suicide because of deeply felt deprivations. In the case of the synthetic humanoid, the development of a consciousness went along similar lines. But there is more to this narrative. The question posed here is, whether a self-conscious machine could or should be considered human. Although the question was the elephant in the room from the first meeting with ZAX onward, it was never explicitly asked. Here now, when the artificial intelligence acquires a human shape – the question becomes an explicit one. The answer remains for the player character to find.

Dr. Zimmer’s position on this is clear. Asked whether owning such an android wouldn’t come down to slavery, he insists that it would still be a machine and could not be enslaved, the same way a generator couldn’t be. 42 While searching for A3-21, though, the player character encounters dissenting voices. Victoria Watts, a contact-person of a group called the “Railroad”, wants the search to end. She asks the Lone Wanderer to convince Dr. Zimmer that A3-21 was dead and explains that the Railroad sees the Commonwealth’s androids as enslaved beings, especially in cases like A3-21’s.

Just understand that this android is now, for all intents and purposes, a man. He looks human, he acts human. He believes he IS human. But even if he's not... Even if he's a machine... He's capable of rational thought. And emotion. So you see, his soul is as human as yours or mine. This person -- and he is a person -- deserves a chance at freedom. Please, if there's a shred of decency in you, don't take that away from him. 43

Later on, after discovering that A3-21 is now living in Rivet City as Harkness, the city’s chief of security, the player character has a variety of options, ranging from informing Dr. Zimmer to deceiving him. But it is also possible to directly talk to Harkness. At first, he doesn’t believe he is an android, claiming: “[…] this is impossible. I can’t be a robot! I’m a human being. I breathe, I eat. Hell, I cut myself shaving this morning. I was bleeding! Robots don’t bleed!” 44 After reactivating his memories, which weren’t removed but deactivated, Harkness is convinced, and thrown into an existential crisis. He likes his ‘life’ in Rivet City and his duties for the community. But he wonders if the community would accept “a machine” living amongst them. It depends on the Lone Wanderer’s actions which path Harkness chooses. He can be convinced to return to the Commonwealth or to stay in Rivet City, to expel Dr. Zimmer or even kill him. If encouraged to stay in Rivet City, Harkness declares: “I have two sets of memories... one android, one human... some of these are mine, some belong to someone else. But I'm choosing to be human. It's my choice. The people on this boat look to me to protect them. So that's what I'm going to do.” Asked why he fled in the first place, Harkness explains:

I don't know... every time I retrieved one of the runaway androids, they'd fill my head with ideas about self-determination, freedom... At first I resisted the ideas... but then, I started thinking about it, and well... they were right. We're just slaves to them. We deserve lives of our own. So that's what I did. I chose a new life, and gave up my old one. And now you've given me both to remember.

Here, we not only see another installment of the established storyline of an AI developing consciousness enriched with the question about its humanity, well known in popular fiction. We also see a hinge around which the AI-storylines in Fallout turn, from sideshow to center stage.

Fallout 4 – Humans behind the AI

Fallout 4, released in 2015, is currently the last main installment in the series. It starts in 2077 and gives the player a short glimpse of pre-war family life, with a Mr. Handy robot named Codsworth taking care of the player-character’s son. When the bombs fall, the player-character, together with his (or her) spouse and son, is evacuated to a nearby vault and put into cryosleep. Exactly 210 years later the player character reemerges as the Sole Survivor into the now devastated Boston area, looking for a son that was abducted while being in cryosleep.

In this title AI technology plays a central role in the narratives surrounding the Sole Survivor. Five of the thirteen companions, characters that will accompany and help the player character, are either robots or androids, commonly identified as Synths (in contrast, only 3 of the possible companions are female). One example is the aforementioned Codsworth, a Mr. Handy robot configured for housework. He is present before the war, and the player can reunite with him after emerging from cryosleep. He then affects a cheerful and composed ‘British butler’ personality, but as the Sole Survivor gains his trust he shows that he is actually deeply affected and depressed by the end of the world. He displays a remarkable range of humanlike abilities; he is capable of deceit, has personal opinions on the player character’s actions – while still being loyal –, and seems to be changed and affected by his personal experiences.

Codsworth, a Mr. Handy robot. Fallout 4. Image obtained from http://fallout.wikia.com/wiki/File:Codsworth_model.png, Copyright by Bethesda Softworks.

Another pre-war robot companion is Curie, a Mr. Orderly 45 assigned to help a team of scientists studying contagious diseases in Vault 81 and given a female personality. Due to staff shortages she is reprogrammed based on the minds of historical great scientists, to be more helpful with the experiments. Through subsequent interaction with the other scientists she develops an independent and self-aware character, but due to her initial programming she is still unable to leave the vault, even after everyone else inside dies. The Sole Survivor can free her from this programming, and after she becomes a companion, she might ask the player for another favor. Curie states that her lack of human ambition is holding her back from achieving true scientific greatness, saying “I have no capacity for the human trait of inspiration.” 46 This leads to a quest in which Curie’s mind is transferred to a synth body. To achieve this the player character has to seek the help of Dr. Amari, a scientist running an establishment that implants memories into humans for entertainment purposes. She finds the problem interesting, stating “The memories wouldn’t be hard. We translate those from the brain to computers and back all the time.” She argues though, that Curie’s personality, the robotic decision making, could not be stored in an organic brain. “A synth brain, on the other hand … Well, it’s already somewhere between the two …” Since she has a mind-wiped synth on hand from another experiment, Curie is ported to the new synth body. There is some initial adjustment to breathing, and then Curie experiences physical grief for her former colleagues and creators.

Curie’s and Codsworth’s stories raise several questions. Both are Mr. Handy robot models, and there are many other Mr. Handy robots the player encounters who show little to no personality or self-awareness. Yet somehow these two robots seem to have developed a whole range of human-like cognitive abilities. With Curie this is partially due to reprogramming, but with Codsworth it just took time to adapt. It is unclear why this has not happened to the other robots around the wasteland. It is also unclear what exact limitation a mind inside a Mr. Handy robot has, and what additional abilities a synth body provides. Finally, it is notable that memories seem to be freely portable between humans, synths and robots.

Another interesting companion is Paladin Danse, a member of the Brotherhood of Steel. He has an intense hatred for all non-humans, including synths. He will mentor the Sole Survivor in the Brotherhood, and repeatedly stress the need to exterminate all synths. The player-character later learns, by accessing the files at the institute, that Danse is indeed an escaped synth himself, who likely had his mind wiped to forget about his past. When the Sole Survivor confronts him he will insist that he did not know he was a synth, and will urge the player-character to kill him, arguing that he needs to be the example, not the exception to the rule.

The game also uses robots and synths for many of their side quests. Mostly as mindless enemies, but there are several encounters that paint a more nuanced picture of AIs. There is, for example, the General Atomics Galleria, an amusement park created by General Atomics to show off their latest developments, such as a militarized version of their popular Mr Handy robot. The park is run by an AI Director who has become unstable, and interaction with the robots will result in the player-character being attacked. The Sole Survivor can convince the director of being its new supervisor, and initiate the grand reopening of the park, turning the robots friendly again. This presents a paradigm that was also used in earlier games, an AI mainframe computer that controls all other robots on site.

The main quest in Fallout 4 revolves around four factions with clashing visions for the future of the wasteland. Towards the end of the game the Sole Survivor has to choose which one to support. The first faction is the Minutemen, who in their dress and mission make allusions to the US founding fathers, and who try to invoke the spirit of the founding fathers in their effort to rebuild society with the existing survivors.

The Institute is another faction, which was already mentioned in the previous game. They are scientists with access to the highest level of technology in Fallout, and they build the synths to do their bidding and build a society to their specifications. They do see the synths as tools, and have used them both as armed soldiers and skillful infiltrators when it suited their needs. They are initially presented as antagonists; especially when it comes to light that they abducted the player-character’s son to obtain an untainted sample of human DNA to build their 3rd generation synth models, which are similar to humans down to the cellular level. The relationship with the Institute gets more complicated once the Sole Survivor learns that the leader of the Institute, an old man by now, is actually the missing son. He gives the player-character access to the Institute’s hidden base and explains the Institute’s vision for the future. The third faction, the Railroad, sees the 3rd generation synths as slaves, and their narrative draws parallels with the abolitionist movement in the US. Their goal is to destroy the Institute to free the synths so they can live like free humans. The final faction, the Brotherhood of Steel, is styled after a monastic order and is interested in preserving lost technology. They are not as technologically advanced as the Institute but focus on military technology, especially aircrafts and power armor. They see the synths as a danger that needs to be eradicated.

Over the course of the game the conflict between the factions escalates, and the Sole Survivor is forced to take sides. One central consideration here is how to deal with the synths. Freeing them requires the player character to destroy both the Institute, which wants to control them, and the Brotherhood, which wants to destroy them. Siding with the latter two basically results in either the destruction or control/enslavement of the synths, and also necessitates the destruction of both other factions, as they would oppose that outcome.

The main ethical question raised in Fallout 3 and Fallout 4 is about the moral status of synths. In ethics, this is often broken down into two different concepts: moral patients, i.e. entities worthy of moral consideration, and moral actors, i.e. entities able to make moral judgements and moral errors. For example, very young children are usually considered to be moral patients but not moral actors. It is less clear if there are inverse example of moral actors that are not moral patients, and consequently, there is a tendency to assume that everything that is able to make moral judgments is also automatically a moral patient.

In Fallout 4 there is relatively little debate about the question if AIs are moral actors. Robots and Synth companions are portrait as having moral preferences, and they might express a like or dislike to the player taking drugs, breaking into places or looking for peaceful solutions to conflict. Curie, the medical research robot, seems to have strong ethical concerns similar to what is expected of human doctors, but it is unclear if this is due to a moral choice of hers, or due to specific, hard-coded moral rules in her programming. While this could be used as a starting point for an in-depth discussion of moral agency this is not really talked about in the game. The focus of the ethical questions that are explicitly asked in Fallout 3 and 4 is about the question of synths and AIs as moral patients – a question that has also recently gained some attention in the public media. 47 In the latest installments of Fallout, this question is portrayed with a relatively clear conclusion. Both sides of the argument are presented in Fallout 3’s quest about the missing android. But on the ludological level of the game-mechanics, there is a clear conception of the right and wrong side of the argument: Fallout 3 has a karma system that rewards the player-character with positive or negative karma points depending on his (or her) moral choices. Returning the android to its owner results in negative karma, while actions that allow the android to flee and keep his freedom are given positive karma. Fallout 4 has no clear moral judgment, but the Institute is universally feared and hated, they use killer robots to terminate whoever stands in the way of their plans, and child abduction and murder seem to be normal actions for them. Joining them is possible, but it feels like an evil option. By association, the idea of synths as tools and property also seems to be hard to defend in the gameworld.

Discussions among real world scientist are less conclusive. In “Robot should be slaves” 48 Bryson argues that to treat robots as servants and not as moral patients has the greatest benefit for all. In her view 49 moral concerns are a product of an evolutionary process that benefits social cohesion, and thereby increases evolutionary fitness. As human society would be better off treating robots like servants, we should not extend moral concerns to AIs. The unease people feel in regards to depictions such as Blade Runner or Mr. Data in Star Trek is the result of overidentification and needless anthropomorphization, as moral concerns arise from identification and empathy. Interestingly, this idea could explain why the Railroad organization in Fallout 4 is very concerned with the freedom of 3rd generation synths, but much less concerned with Mr. Handy robots, even though Curie's story demonstrates that their minds seem to be interchangeable.

Bostrom and Yudkowsky 50 take a more principled approach. In their view moral status arises as a result of certain mental properties. They in particular talk about sentience 51 and sapience 52 – all qualities that were demonstrated by Fallout’s AIs at one point or another. The usual idea here is that the ability to feel and to suffer should grant one the moral right to be spared from needless suffering, while the ability to reason and be self-aware awards one with a right to autonomy and freedom. So animals are usually awarded a lesser moral status than humans; they should be spared from needless cruelty, but they don’t have many other rights. They also point out that it would be possible for AIs to have sapience without sentience – for which there is no existing example in the real world. This would provide an interesting challenge, as it would force people to consider what exact property or set of properties bestows what ethical status? This also shows how Fallout 4 avoids the hard question here. The depiction of synths is human in anything but origin, their look and their stories fully exploit the misplaced empathy mentioned by Bryson. Fallout 4 basically gives us AIs with all mental properties of humans, be it consciousness, creativity, emotions, suffering, faith, etc. We are not forced to figure out what exactly makes AIs, and by extension us, worthy of ethical concern, as synths basically qualify for every possible answer.

Conclusion

Looking at the series as a whole, we can clearly see how the prominence of AIs and AI-driven storylines increases over time. The first two games barely had a handful of AIs, portrayed mostly as outdated mainframes. As one of the developers stated, this already was a departure from the original idea, to base the world of Fallout on the visions of the future that were dominant during the 1950s – where there were next to no AIs. But they made it into the game world nonetheless, representing popular narratives about AIs as well as current technological questions from the 1990s, when the first two games were developed. The latter two games on the other hand, produced by a new studio and ten years later, have an abundance of AI characters, which serve as antagonists, quest givers and focal points of central plot developments. In addition, many of the portrayed AIs are autonomous mobile units, or even human-like androids. The increased presence of AIs seems to reflect their increased presence in the real world. Their stories, though, remained rooted in the established popular narratives from the 1990s – while new references to current technological questions were now absent.

The second main development is the increased focus on the ethics of artificial intelligence. ‘Are AIs moral patients?’ could be the tagline for the fourth game, it is an important topic discussed in the third game and hinted at in the second. As discussed, the answer to this question depends significantly on the philosophy of artificial intelligence. Does consciousness qualify one for ethical treatment, and what proves one is conscious, or at least ‘truly’ intelligent, and not just a thinking machine? The AIs in Fallout display a lot of the usual candidate criteria, such as emotions, motivations, creativity, the ability to suffer, personalities based on individual experience, the ability to learn and adapt, etc. In the end it often seems to boil down to some kind of behavioral criteria – a Turing Test of some sort. Convince a human that you are worthy of ethical consideration, and it will likely be granted. For the question of how those abilities come about, the games lean on the idea of adaptation and learning. Most interesting AIs in the game changed and improved over time and at some point in this development they somehow acquired these hard to explain abilities. There seems to be a consistent narrative here that a lot of those consciousness-related properties are a necessary byproduct of an adaptation to greater intelligence.

Both of the previous stances are human-centric. There are no truly alien intelligences in the Fallout universe; all the AIs that adapt never become godlike or incomprehensible. Instead they turn from calculation machine into minds that feel and act a lot like humans, that try to look, interact and speak like humans. The final stage of the synth program is basically a robot that is identical to humans on a molecular level. This is good for the narrative, as it allows one to ask the moral question of why one would treat an entity, which is human in all but name that only differs in some minor, arbitrary detail of being synthetic, any different? This is in the best tradition of stories such as Blade Runner or the Bicentennial Man, and evokes societal comparison to slavery and women's rights. But on the other hand, it limits the moral question strictly to these well-established aspects of stories about AIs – and in the end even dodges the really hard ethical questions: What about artificial minds that are radically different from ours? What are the actual and necessary criteria for something that is not considered to be human to deserve a certain kind of moral treatment or even its own set of rights and freedoms?

References

Games

Bethesda Games Studios: Fallout 3. Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks 2008.

Bethesda Games Studios: Fallout 4. Rockville, USA: Bethesda Softworks 2015.

Black Isle Studios: Fallout 2. A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game. Los Angeles, USA: Interplay Entertainment 1998.

Interplay Productions: Fallout. Los Angeles, USA: Interplay Productions 1997.

Interplay Productions: Wasteland. Redwood City, USA: Electronic Arts 1988.

Movies

Badham, John: WarGames. USA: Goldberg, Leonard; Hashimoto, Rich; Schneider, Harold K.; McNall, Bruce 1983.

Jonze, Spike: Her. USA: Ellison, Megan; Jonze, Spike; Landay, Vincent 2013.

Kubrick, Stanley: 2001: A Space Odyssey. UK: Kubrick, Stanley 1968.

Scott, Ridley: Blade Runner. USA: Deeley, Michael 1982.

Texts

Aleksander, Igor: Impossible Minds. My Neurons, My Consciousness. Bartow, Fla: Imperial College Press 1996.

Avellone, Chris: Fallout Bible: Section Zero. Jan 15th – Feb 25th 2002. s.l.: 2002. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]

Avellone, Chris: Fallout Bible Update 6. July 10th 2002? s.l.: 2002. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]

Avellone, Chris: Fallout Bible Updeight. September or October 2002 or something. s.l.: 2002. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]

Avellone, Chris: Fallout Bible Nein. October 15? Nov 6? 2002? Ah, screw it. s.l.: 2002. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]

Bidshahri, Raya: If Machines Can Think, Do They Deserve Civil Rights? Singularity Hub. (09.11.206). <https://singularityhub.com/2016/09/09/if-machines-can-think-do-they-deserve-civil-rights/> [15.04.2017]

Bostrom, Nick: The Superintelligent Will. Motivation and Instrumental Rationality in Advanced Artificial Agents. In: Minds and Machines. 22, 2 (2012), pp. 71-85.

Bostrom, Nick; Yudkowsky, Eliezer: The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. In: Ramsey, William; Frankish, Keith (Eds.): The Cambridge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 316-334.

Bryson, Joanna J.: Robots Should be Slaves. In: Wilks, Yorick (Ed.): Close Engagements with Artificial Companions. Key Social, Psychological, Ethical and Design Issues. Amsterdam: Benjamins 2010, pp. 63-74.

Bryson, Joanna J.; Kime, Philip P.: Just an Artifact. Why Machines are Perceived as Moral Agents. In: The Twenty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI). 22, 1 (2011), pp. 1641-1646.

Chella, Antonio; Manzotti, Riccardo: Artificial Consciousness. 2nd ed. Luton: Andrews UK 2013.

Froese, Tom; Ziemke, Tom: Enactive Artificial Intelligence. Investigating the Systemic Organization of Life and Mind. In: Journal of Artificial Intelligence. 173, 3-4 (2009), pp. 466-500.

Gradischnig, Thomas Johannes: Narrative Strukturen und Funktionen im Computerspiel am Beispiel Fallout 3. Diplomarbeit. Wien: Universität Wien 2011.

Harkness‘ Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Harkness%27_dialogue> [27.02.2017]

Heinlein, Robert A.: The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. New York, NY: G. P. Putnam's & Sons 1966.

Heller, Nathan: If Animals Have Rights, Should Robots? In: The New Yorker. (28.11.2016). <http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/11/28/if-animals-have-rights-should-robots> [15.04.2017]

Meissner, Steven: Just How Realistic is Fallout 4's Post-Apocalypse Anyway? s.l. 2015. <https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/just-how-realistic-is-fallout-4s-post-apocalypse-anyway> [15.04.2017]

Minsky, Marvin; Papert, Seymour: Perceptrons. Oxford: MIT Press 1969.

Moravec, Hans: Mind Children. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1988.

Murray, Jerome T.; Murray, Marilyn J.: The Year 2000 Computing Crisis. A Millennium Date Conversion Plan. New York: McGraw-Hill 1996.

November, Joseph A.: Fallout and Yesterday’s Impossible Tomorrow. In: Kapell, Matthew Wilhelm; Elliott, Andrew B. R. (Eds.): Playing with the Past. Digital Games and the Simulation of History. New York, London: Bloomsbury Academic 2013, pp. 297-312.

Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves; Kaplan, Frederic: What is Intrinsic Motivation? A Typology of Computational Approaches. In: Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 1 (2009), pp. 1-14.

Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter: Artificial Intelligence. A Modern Approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall 1995.

Saygin, Ayse Pinar; Cicekli, Ilyas; Akman, Varol: Turing Test. 50 Years Later. In: Minds and Machines. 10, 4 (2000), pp. 463-518.

Schulzke, Marcus: Refighting the Cold War. Video Games and Speculative History. In: Kapell, Matthew Wilhelm; Elliott, Andrew B. R. (Eds.): Playing with the Past. Digital Games and the Simulation of History. New York, London: Bloomsbury Academic 2013, pp. 261-275.

Searle, John R.: Minds, Brains, and Programs. In: Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 3, 3 (1980), pp. 417-424.

Strecker, Sabrina: Longing for the Past. Von Retro-Kultur und Nostalgie in Fallout: A Post Nuclear Role Play Game. In: Letourneur, Ann-Marie; Mosel, Michael; Raupach, Tim (Eds.): Retro-Games und Retro-Gaming. Nostalgie als Phänomen einer performativen Ästhetik von Computer- und Videospielkulturen. Glückstadt: Verlag Werner Hülsbusch 2015, pp. 189-203.

Turing, Alan M.: Computing Machinery and Intelligence. In: Mind. 59, 236 (1950), pp. 433-460.

Victoria Watts‘ Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Victoria_Watts%27_dialogue> [27.02.2017]

Weizenbaum, Joseph: ELIZA – a Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine. In: Communications of the ACM. 9, 1 (1966), pp. 36-45.

Wimmer, Jeffrey: Moralische Dilemmata in digitalen Spielen. Wie Computergames die ethische Reflexion fördern können. In: Communication Socialis. 47, 3 (2014), pp. 274-282.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer: Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk. In: Bostrom, Nick; Ćirković, Milan M. (Eds.): Global Catastrophic Risks. New York, NY: Oxford Univesity Press 2008, pp. 308–345.

Zimmer’s Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Zimmer%27s_dialogue> [27.02.2017]

- Interplay Productions: Fallout. 1997. [↩]

- The setting of the game leans on: Interplay Productions: Wasteland. 1988. [↩]

- Interplay Productions: Fallout. 1997. [↩]

- Black Isle Studios: Fallout 2. 1998. [↩]

- Bethesda Games Studios: Fallout 3. 2008. [↩]

- Bethesda Games Studios: Fallout 4. 2015. [↩]

- Strecker: Longing for the Past. 2015; see also Avellone: Fallout Bible Update 6. 2002, p. 18. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]; Avellone: Fallout Bible Updeight. 2002, pp. 18-20. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]; Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 4. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Meissner: Just How Realistic is Fallout 4's Post-Apocalypse Anyway? 2015. <https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/just-how-realistic-is-fallout-4s-post-apocalypse-anyway> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Schulzke: Refighting the Cold War. 2013, passim.[↩]

- November: Fallout and Yesterday’s Impossible Tomorrow. 2013, pp. 297-301, 303-308. [↩]

- One of the developers of the first two Fallout-games stated that AIs weren’t supposed to play a major role in Fallout, because they weren’t a big thing in the future as seen from the 1950s, Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 4. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- That inclination to questions of morals is a fundamental feature of the games that always include the line “War. War never changes.” into their introductory sequences. For morals in computer games see also Wimmer: Moralische Dilemmata in digitalen Spielen. 2014. [↩]

- This is one of the main objections levelled against the AI-storylines by Chris Avellone, that “they're too 1990s/21st century”, Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 7. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- The developers only confirmed it was post-World-War-Two, Avellone: Fallout Bible Update 6. 2002, p. 4. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- The quotes in this section, if not marked otherwise, stem from Interplay Productions: Fallout. 1997. [↩]

- Murray: The Year 2000 Computing Crisis. 1996. [↩]

- Turing: Computing Machinery and Intelligence. 1950. [↩]

- Weizenbaum: ELIZA – a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. 1966. [↩]

- Jonze: Her. 2013. [↩]

- Compare movies such as Wargames and 2001. A Space Odyssey, or books such as The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress. [↩]

- Moravec: Mind Children. 1988. [↩]

- The name refers to VAX, a robot in Wasteland, Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 28. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]; see also Avellone: Fallout Bible: Section Zero. 2002, pp. 15-16. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Avellone: Fallout Bible Update 6. 2002, p. 22. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]; Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 29. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Different dates are given in Avellone: Fallout Bible: Section Zero. 2002, pp. 15-16. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]; later corrected in Avellone: Fallout Bible Update 6. 2002, p. 5. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Russell: Artificial Intelligence. 1995, p. 24.[↩]

- Minsky: Perceptrons. 1969. [↩]

- Aleksander: Impossible Minds. 1996. [↩]

- In Fallout 3 a hint is given that it was intended to shut ZAX down in 2078 – so it seems probable that it was never planned to let it develop its full potential, but the war allowed it to do so. [↩]

- Chella: Artificial Consciousness. 2013. [↩]

- This and all other unattributed quotes in this section stem from Black Isle Studios: Fallout 2. 1998. [↩]

- Searle: Minds, Brains, and Programs. 1980, pp. 417-424. [↩]

- For a more detailed discussion, see chapter 26.4 in Russell: Artificial Intelligence. 1995. [↩]

- Skynet isn’t the AI’s official name, as one of the developers stated, Avellone: Fallout Bible Nein. 2002, p. 7. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- According to the developers that is wrong, it became self-aware in 2075 (with no explanation given), Avellone: Fallout Bible Update 6. 2002, p. 23. <http://www.duckandcover.cx/?id=5> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Yudkowsky: Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk. 2008. [↩]

- Bostrom: The Superintelligent Will. 2012. [↩]

- Oudeyer: What is Intrinsic Motivation? 2009. [↩]

- Froese: Enactive Artificial Intelligence. 2009. [↩]

- See Gradischnig: Narrative Strukturen und Funktionen im Computerspiel am Beispiel Fallout 3. 2011, pp. 24-27, 72-77, 85-100, 103-113; see also November: Fallout and Yesterday’s Impossible Tomorrow. 2013, pp. 301-303. [↩]

- Saygin: Turing Test. 2000. [↩]

- As the game was only available in the German version, the quotes used here stem from Zimmer’s Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Zimmer%27s_dialogue> [27.02.2017]. [↩]

- Note that Zimmer always uses the personal pronoun “he” when talking about A3-21, instead of “it” as would be normal for a tool or machine, thereby contradicting his own argument and pushing the player into the direction of seeing the android as a person from the start. [↩]

- Quotes taken from Victoria Watts‘ Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Victoria_Watts%27_dialogue> [27.02.2017]. [↩]

- Quotes are taken from Harkness‘ Dialogue. <http://fallout.gamepedia.com/Harkness%27_dialogue> [27.02.2017]. [↩]

- A modified Mr. Handy for assistance in hospitals. [↩]

- This, and all subsequent quotes in this section are taken directly from the game Fallout 4. [↩]

- Heller, Nathan: If Animals Have Rights, Should Robots? 2016. <http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/11/28/if-animals-have-rights-should-robots> [15.04.2017], Bidshahri, Raya: If Machines Can Think, Do They Deserve Civil Rights? 2016. <https://singularityhub.com/2016/09/09/if-machines-can-think-do-they-deserve-civil-rights/> [15.04.2017]. [↩]

- Bryson: Robots Should be Slaves. 2010. [↩]

- Bryson: Just an Artifact. 2011. [↩]

- Bostrom: The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. 2014. [↩]

- The capacity for phenomenal experience or qualia, such as the capacity to feel pain and suffer. [↩]

- A set of capacities associated with higher intelligence, such as self- awareness and being a reason-responsive agent. [↩]